This is the 2019/20 edition of State of Care

Across all sectors, some people were not able to access the care they need when they need it. Inspectors and external stakeholders have highlighted challenges in all sectors, including:

- Pressures on emergency departments due to local demand, often linked to access issues elsewhere in the system. For some people, A&E can be the way to get the care they need, either because it is more convenient than attending their GP surgery, they are not registered with a GP, or they are unaware of other services available.

- NHS trusts struggling to meet referral-to-treatment times – the total number of people waiting for treatment carried on rising, reaching 4.4 million in February 2020. We heard about long waiting times for ophthalmology and people experiencing difficulties accessing cancer treatment, orthopaedics, dermatology, gynaecology and physiotherapy.

- Difficulties accessing child and adolescent mental health services, with long waiting times for those with neurodevelopmental conditions, and long waiting lists for children who have been sexually abused to receive counselling support.

- Difficulties across the country for people who need residential care with nursing – this was linked to workforce challenges, with the recruitment of nurses a particular challenge for the sector. A related issue is a lack of suitable provision for people with high support needs, including people living with dementia.

- Lack of access to high-quality, person-centred home care, especially in rural locations; a reliance on a few large providers in some areas poses significant risks if these providers struggle to meet demand.

- Long waits for social care assessments and support, and in some localities people only had access to poor quality services.

- General problems for people in getting routine GP appointments – there was a long-term decline in people saying it was easy to get through to the practice on the phone, from 81% in 2012 to 65% in 2020 – and difficulties for some people with substance misuse or mental health issues in registering with a GP.

- Difficulties accessing NHS dental care, and the cost of dental treatment being a barrier to access for some people; and difficulties accessing dental care for people living in residential care settings and those in custody.

- Despite prompt assessment of acute need, poor access to secure mental health beds meant that adult prisoners remained in inappropriate custodial settings for prolonged periods, awaiting transfer.

Staffing issues in all regions have been a key factor affecting access to services. Inspectors and external stakeholders have heard about services competing for staff, with smaller services and those in rural or deprived areas facing particular challenges filling vacancies. Local factors can affect staff recruitment and retention, such as:

- higher rates of pay in London attracting people from neighbouring regions to work in the capital

- alternative opportunities in popular tourist spots during the summer affecting the social care workforce

- areas that do not have universities or training colleges nearby limiting the graduate recruitment market. Recruitment to health services in the criminal justice and immigration detention sectors is particularly challenging, leading to high use of agency staff in many services.

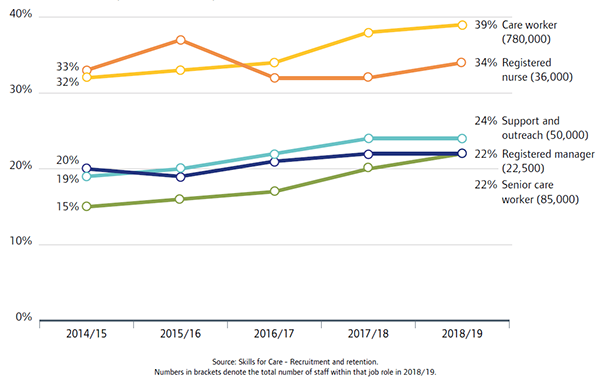

People who use services and care professionals who shared their experiences with us through our online form have raised their concerns about low staffing levels in care homes. People felt that the safety and quality of care that residents in care homes experienced was reduced, as was their continuity of care when staff were leaving. The most recent data from Skills for Care shows how turnover rates for care workers and senior care workers have risen steadily over many years.

Issues around access to good quality care have also featured prominently in the experiences that people have shared with us through our online form. These included: problems for individuals struggling with poor mental health in accessing appropriate support, especially in the community, leading to a further decline in their wellbeing; issues with being able to book suitable primary care appointments, leading to a loss of confidence in services; and people being left frustrated and in pain when they struggled to access the right medical care and treatment. Also prominent in the experiences people have shared with us have been in adult social care services, with issues around poor personal care, hygiene and nutrition, and injuries such as fractures and pressure sores caused by poor care.

In the face of these challenges, we did hear about a range of positive initiatives to improve access to care. For example:

- In general practice: extended opening times, care navigators, advanced nurse practitioner-led services, increased use of telephone and video appointments, social prescribing schemes, and GP practices actively engaged in outreach work.

- In dental care: a mobile surgery visiting a children’s home to help young people overcome their fear of seeing a dentist, and using oral needs analysis to secure more funding and improved access to dental care in prisons.

- In hospitals: work to reduce demand on emergency departments, including GP triage, and to improve access for people with protected equality characteristics and those in vulnerable situations, for example clinics for sex workers.

- In mental health care: GP practices commissioning in-house mental health services, and upskilling police officers to signpost people to appropriate local services.

- In adult social care: multidisciplinary collaboration including contracts between care homes and GPs to make GP access easier in residential care and nursing home settings.

- For children and young people: digital services that are proving beneficial for mental health and wellbeing by providing access to online counselling or therapeutic input, and face-to-face drop-in services for young people.

A fundamental change is needed for people with a learning disability and autistic people who need complex care

In our work looking at the use of restraint, seclusion and segregation in care settings for people with complex needs, it was clear that for people in segregation creating a package of care to meet their individual needs was often seen as too difficult to get right and they had fallen through the gaps.

Not getting the care and support in the community when people needed it started at a young age. This lack of support in the community often led to people becoming increasingly distressed. When people reached ‘crisis point’, hospital was often the only option left – but hospital wards are not therapeutic environments for people with a learning disability and/or autistic people.

Complex commissioning arrangements and poor communication between providers and commissioners could lead to delays in identifying suitable community care or getting the care package ready. These delays and failed placements could lead to a deterioration in people’s wellbeing and behaviour. As a result, people could find themselves being moved into more secure and restrictive environments, and could lead to them becoming ‘stuck in the system’.

It is possible to, and we as a system can, do much better. We will be publishing the full findings from our review in October 2020 and we will be calling for immediate and tangible progress to be made.

Much better access was needed to mental health care and support

We have previously highlighted the difficulties that some people have had in accessing the right mental health care and support at the time they need it. Alongside this State of Care report, we are updating on three pieces of work that show there was limited progress in improving access for people.

- Inpatient rehabilitation services: From 2017 to 2019, there had been only a small increase in the number of people receiving inpatient rehabilitation care close to home, and too many people continued to be sent far from home for treatment. People being cared for by independent providers were still staying longer in hospital, and were further away from home, than those in NHS services.

We remain concerned at the high number of wards that continued to identify as ‘locked rehabilitation’ – this is against the least restrictive principle that mental health services should apply and potentially represents a breach of human rights. - Children and young people’s mental health care: In following up the 2018 recommendations for local action that we made about access to mental health care for children and young people, we found that these were being implemented in varying degrees in the health and wellbeing areas who responded to our self-assessment questionnaire. For example, while our findings indicated there was stronger prevalence of joint commissioning, almost one in five local health and wellbeing boards reported back that there was no joint commissioning of support for teenagers and young people as they move to adult services.

- Mental health care in acute trusts: Between September 2017 and March 2019, we looked at how well NHS acute trusts were meeting the mental health needs of people – in emergency departments, acute medical wards, maternity wards, and children and young people’s services. Staff we met were caring and working very hard in challenging circumstances, but often they felt unsupported and unprepared to care for the mental health needs of their patients. We found that mental health training for staff varied across the trusts.

A lack of availability of community crisis services meant people were frequently left with no other option than to attend the emergency department. Once in hospital, we found that there was poor coordination and joint working between acute and mental health services, with delays in assessments and securing beds.

Patients were not always provided with a safe, therapeutic environment. Every hospital emergency department should have a dedicated room that is equipped to provide a safe and private environment for psychiatric assessments. The safe rooms we saw did not always meet these standards. We also found that people in crisis were not given information about when they would be seen, or how long they would have to wait for an assessment or admission to hospital.

Next page

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

Previous page

Some of the poorest quality services were struggling to make any improvement

This is the 2019/20 edition of State of Care.

Go to the latest State of Care.

Contents

Quality of care before the pandemic

- Quality overall before the pandemic

- Care that is harder to plan for was of poorer quality

- Care services needed to do more to join up

- Adult social care remained very fragile

- Some of the poorest quality services were struggling to make any improvement

- There were significant gaps in access to good quality care

- Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

- Inequalities in care persisted

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic

- The impact on people

- The impact on health and social care staff

- Infection prevention and control

- The unequal impact of COVID-19

- The impact of COVID-19 on DoLS

- Innovation and the speed of change

Collaboration between providers

- How did care providers collaborate to keep people safe?

- System-wide governance and leadership

- Ensuring sufficient health and care skills where they were needed

- The impact of digital solutions and technology