This is the 2019/20 edition of State of Care

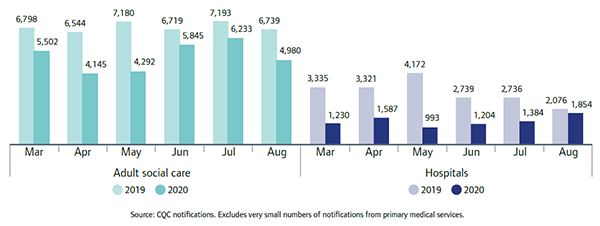

During the pandemic, we continued to monitor notifications to us of the outcome of a Deprivation of Liberty Safeguard (DoLS) application. It is important to note that this may not necessarily reflect a drop in applications made, as providers need only notify CQC once they know the outcome, not when they make the application. From March to May, we saw a sharp fall in the number of notifications compared with the same period in 2019 (figure 13). Notifications from adult social care services dropped by almost a third (31%), and in hospitals by almost two-thirds (65%), compared with the same period in 2019. By July, the numbers received from adult social care services had risen again, although they fell back in August.

There was variation between regions. In adult social care, London saw the largest percentage change with a 37% drop in March to May 2020 compared with 2019, while the South West fell by 25%. For hospitals, the South East saw the largest percentage reduction in March to May of 82%, while the South West and East of England regions each fell by 52%.

In line with government guidelines for COVID-19, adult social care providers and hospitals introduced new restrictions to enable people to be isolated and/or socially distanced. This included restricting access in and out of buildings and implementing enhanced infection control.

Providers had to introduce certain restrictions into an already complex and confusing picture, with the lack of understanding about DoLS potentially having an impact on providers’ confidence about whether such restrictions amount to a deprivation of liberty or not. To help providers, in April 2020 the Department of Health and Social Care introduced specific guidance on looking after people who lack mental capacity. This explained that, during the pandemic, no legislative changes to the Mental Capacity Act were being made. Providers would still need to apply for a DoLS if the conditions were met. The guidance also set out pertinent case law and considered the relevancy of specific public health powers in some limited cases.

The pandemic also introduced an additional challenge for providers, in balancing restrictions to keep people safe from COVID-19 with ensuring that they are applying the less restrictive principle in line with the Mental Capacity Act. Some providers continue to actively mitigate the impact of COVID-19 restrictions, aware that some people with complex conditions, such as dementia, are particularly at risk of isolation.

This includes, for example:

- buying screens and encouraging people who use services to video call their families

- introducing ‘relay walks’, where services stagger access to communal areas of a care home (while maintaining appropriate infection control) – this encourages mobility and allows people to spend more time outside of their room.

We will continue to monitor how services are managing this balance and following the relevant guidance as it evolves.

Next page

Innovation and the speed of change

Previous page

This is the 2019/20 edition of State of Care.

Go to the latest State of Care.

Contents

Quality of care before the pandemic

- Quality overall before the pandemic

- Care that is harder to plan for was of poorer quality

- Care services needed to do more to join up

- Adult social care remained very fragile

- Some of the poorest quality services were struggling to make any improvement

- There were significant gaps in access to good quality care

- Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

- Inequalities in care persisted

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic

- The impact on people

- The impact on health and social care staff

- Infection prevention and control

- The unequal impact of COVID-19

- The impact of COVID-19 on DoLS

- Innovation and the speed of change

Collaboration between providers

- How did care providers collaborate to keep people safe?

- System-wide governance and leadership

- Ensuring sufficient health and care skills where they were needed

- The impact of digital solutions and technology